This is a story of game design by accident, and of how it might save us from emergencies of our own making.

In the 1950s, the United States was undergoing rapid urban growth, but modern urban planning was in its infancy. Planners struggled to progress beyond the traditional focus on the neighborhood-level physical environment and tackle their work’s larger social, economic, environmental, fiscal, and political aspects.

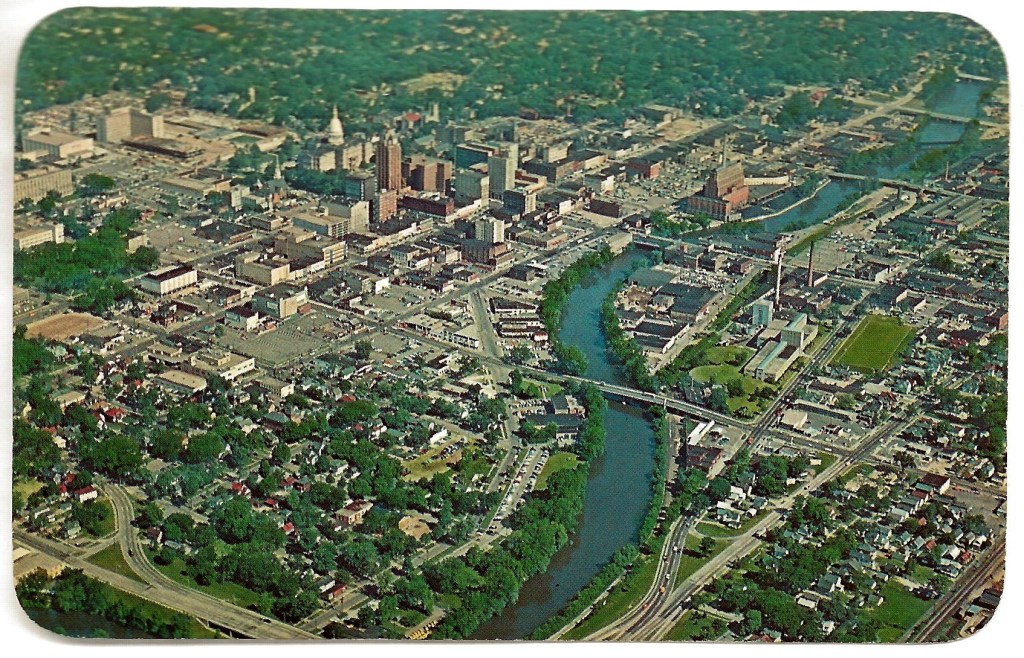

At the time, Richard de la Barre “Dick” Duke was teaching the subject at Michigan State University. He and his colleague Stuart Marquis teamed up in 1958 to develop a program that would turn Lansing, Michigan into a laboratory community for exploring the underscrutinized dimensions of urban development.

By 1960, the pair had collected an array of relevant information. This trove was, understandably, not internally coherent and “inherently dry” (Duke “Gaming: An Emergent Discipline” 427). Duke felt the project could succeed only by making the materials livelier and more engaging.

Duke tried a novel experiment: he assigned each student the role of a significant community figure (developer, builder, mayor, city council member, head of a citizens’ group, etc.). The students would research and synthesize the relevant information from their assigned perspective and represent it in class discussions. Duke describes the result as “a dynamic interactive style of teaching” (“Gaming: An Emergent Discipline” 427).

Marquis suggested Duke contact Richard E. Meier, a professor at University of Michigan. Duke described the Lansing project, and Meier’s immediate and enthusiastic response was “What you have designed is a game!” (Duke “Origin and Evolution of Policy Simulation” 3).

Meier, of all people, would know. He had participated in a Washington DC think tank that had used wargaming and simulation to develop military strategies during World War II. He described to Duke the state of gaming at the time (referred to then as operational-gaming or simulation-gaming), directed him to war and business games to study, and emphasized gaming’s potential to improve communication and develop real solutions to critical policy issues. Duke would go on to do his doctoral studies under Meier, earning a PhD in resource economics in 1966.

In the interim, Duke continued working on the Lansing project. The years 1962–3 saw his earlier experiment formalized as METROPOLIS, a simulation of the greater Lansing urban area that incorporated current and historical socioeconomic data into the existing political context. During its development, Duke initially paid students to playtest it. When word got out, students volunteered to test it for free. And finally, Lansing paid Duke $100 (over $1,000 in 2024 dollars) to present it to the city council.

Students and councilmembers thoroughly enjoyed the game, but just as importantly, they and Duke all recognized that it improved understanding of, and conversations about, budget decisions. It proved that, beyond business and war, gaming provided a valuable tool for making educated policy decisions and for future-oriented planning in other fields.

With his PhD and first game in hand, Duke suddenly found himself in high demand. Universities in the US and Europe invited him to demonstrate METROPOLIS. His professional interests strayed from traditional urban planning into the emergent discipline of gaming and simulation. Over the course of his decades-long career, he would go on to develop games for public institutions (including several for the United Nations) as well as private corporations (such as Xerox, Proctor & Gamble, Marriott, and Conrail).

Duke’s practical work in gaming is a historical landmark, and throughout his career, he mentored other designers and helped facilitate the growth of professional design networks in the US and Europe. But one of his greatest contributions was the publication of a combined design textbook and theory of gaming. That theory is the subject of the next post.

This article was originally written on spec for Wyrd Science magazine.

The header is a mashup of images by giannsartori and Kelly. Both are open license.

Related posts

Reminiscences of the Future, Part 2: A Theory of Gaming

Richard Duke’s philosophy of gaming against disaster & dystopia

Reminiscences of the Future, Part 3: Gaming Against Disaster & Dystopia

Richard Duke’s philosophy of gaming against disaster & dystopia

2 thoughts on “Reminiscences of the Future, Part 1: Game Design by Accident”