In 1958, Richard Duke unintentionally began dabbling in gaming as a method for teaching the complex subject of urban planning. Over the course of the next decade, he became a world-renowned designer after creating METROPOLIS, a simulation using Lansing, Michigan as a model for exploring urban development and policy issues.

The Gaming Wheel

While in Hawai’i in 1972, a serious scuba diving accident landed Duke in the hospital. He was bedridden for the better part of a year and left with nothing to do but contemplate gaming. Duke began searching for underlying commonalities in purpose, structure, and design, seeking a theory that explained gaming’s effectiveness as an educational and communications tool. He identified common elements, wrote them on small pieces of paper, and had nurses and visitors arrange them on his hospital room’s wall. The result was what he called the gaming wheel, and it would be the basis for his 1974 book Gaming: The Future’s Language.

1974 was, of course, the year that TSR published the first iteration of Dungeons & Dragons, which grew from wargaming in parallel with the policy games Duke designed and studied. I’ve found no evidence that Duke either was or was not aware of D&D and subsequent RPGs, but regardless, his theory of games and their utility describes how, beyond providing entertainment, TTRPGs can educate and contribute to social change.

Gaming describes itself as “an attempt to develop a unifying perspective on the nature of gaming and to do so in a context broad enough to include all serious gaming activity” (xiv). But it is also Duke’s manifesto for his “unshakeable belief that someday, somehow, properly used, games were going to change the world” (“Gaming: An Emergent Discipline” 429).

The world was already changing rapidly, but not for the better. Duke believed gaming could correct the course toward a future that would benefit humanity as a whole. But that could only happen by reclaiming personal agency in socio-politics, which is eroded by false dichotomies, professional elitism, dependence on technology, and gigantism.

False dichotomies are the proverbial simple answers to complex problems. Because real problems are too nuanced and multifaceted for an individual to comprehend by traditional methods, policy decisions focus on isolated aspects that are cast as reductive either-or situations that fail to capture the totality of the reality they seek to address. At best, resulting decisions are inefficient; at worst, they’re irrelevant and may lead to new problems.

Professional elitism is communication-as-gatekeeping. In any advanced field, jargon abounds; it allows professionals to converse more efficiently with one another, but it obscures the topic from the uninitiated. If a layperson can’t understand an issue, they can’t participate in the conversation, and so the resolution will not account for their real needs.

Dependence on technology is exactly that: reliance on a material culture that is cold and indifferent to human concerns. Professional elitism guarantees that people must rely, day to day, on technology they cannot comprehend.

Gigantism is the tendency toward bureaucratic bloat. Government institutions and large corporations grow so vast and sprawling that no single individual can comprehend their total internal workings. Consequently, the decision-making process must pass through so many steps and hands that the organization can’t efficiently correct problems and respond to emergencies.

Trammeled under the paw of this four-headed chimera, the individual finds themself unable to effectively contribute to and guide change. Their only recourse is to “join together with fragmentary bands to throw slingshots at the giant” (Gaming: The Future’s Language 5)—the common sight of activists and protesters marching through the streets, occupying public spaces, and rallying at capitols. Predictably, however, the outcome is a standoff, and the status quo persists due to the institution’s failure to take any action at all.

Duke proposes a solution: a more sophisticated mode of communication. Traditional modes are sequential and ill suited for addressing the complexities found in our modern lives. If we cannot adequately comprehend and discuss those complexities, then we are unprepared to take effective action.

The Future’s Language

Games are uniquely suited to making complexity manageable and intelligible. Duke writes “their purpose is to explore alternatives, to develop a sophisticated mental response to ‘what if’ questions, and to permit the formulation of analogy for exploration of alternatives where no prior basis for analogy exists” (Gaming: The Future’s Language 52).

In Gaming, Duke sketches a continuum of communications. It starts at the primitive mode, which can convey relatively simple messages through informal means (simple gestures or nonverbal utterances) or formal ones (like semaphore or international symbols). The advanced mode includes spoken conversations and lectures, written documents, mathematical and musical notations, and the various arts like sculpture, painting, performance, etc. These can convey nuanced affects and more intricate ideas.

Primitive and advanced forms of communication are sequential, defined by linearity. The simplest sequential form is the monologue, a one-way communication from sender to receiver (such as in a book). Dialogue is an “interrupted serial message” (Gaming: The Future’s Language 33) wherein participants are both sender and receiver in alternating sequence (like in an everyday conversation). A sequential dialogue occurs when multiple sender-receivers interact in a segmented sequence (such as a moderated panel discussion or a Q&A session after a presentation).

At the higher end of the continuum are integrated communications. The first integrated form is multimedia, which combines the discrete forms of advanced communication (for example, a slideshow in tandem with a lecture). The second is “future’s language,” which includes flow charts, maps, architectural models, and gaming. These forms are characterized by nonsequential communication and various degrees of interactivity that empower participants to develop gestalt understanding—comprehension of the larger, complex reality that these media present in abstracted forms.

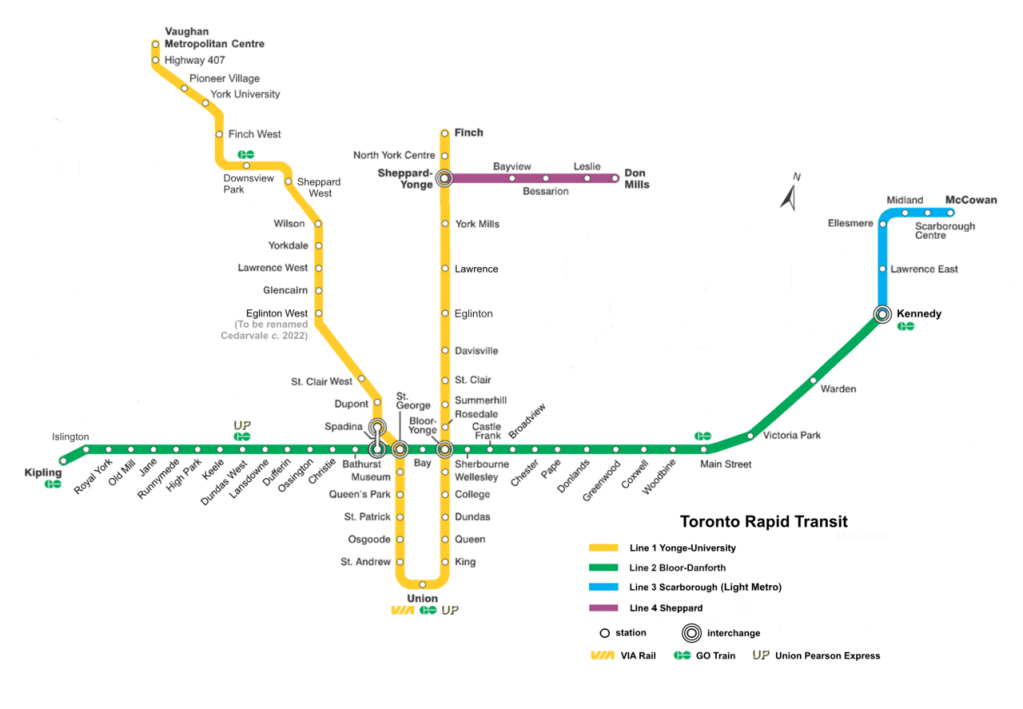

Consider, for example, a subway map, which combines words and images and has no arbitrary beginning or end. The user engages with it at a logical entry point (“I am at point A”) and uses it to solve a problem (“I need to get to point B”). The user gradually develops an internalized image of the subway’s composition and shape that allows them to solve relevant problems (“Today, I need to get to point Q”) on their own. In contrast, a hypothetical sequential map (whatever that might look like) would describe the subway system in a purely linear way that would be mostly unusable for solving relevant problems and developing a holistic mental model of the transit network.

Gaming works similarly. Players bring to the game their own perspective, whatever it is, and develop it through in-game interactions. This takes the form of multilogue: multiple, simultaneous, and constantly shifting dialogues. These dialogues are unified into a multilogue by a pulse—a problem situation that participants must explore and resolve. Iterative pulses are meaningfully related and build upon one another, giving players feedback that enables them to better understand the system’s gestalt. In doing so, they develop heuristics: cognitive models and strategies for solving relevant problems.

Duke calls this approach a “future’s language” not because he predicts we’ll someday exclusively communicate using forms in this mode, but because these forms are future oriented. They develop personal, internalized comprehension of complex reality that participants can use to solve emergent problems. Sequential forms are past oriented and convey information that likely won’t be relevant to decision-making in radically new situations. But through gaming, we can explore possible futures in a risk-free environment, developing knowledge relevant to real, large-scale problems.

To empower players in this way, a particular game must incorporate accurate conceptual maps built around specific problems: “players are present because they share a desire to explore some problem; and … the game is especially invented to facilitate discussion of that problem” (Gaming: The Future’s Language xvii).

What problems do RPGs confront their players with? We’ll take a look at four case studies in this series’ final post.

This article was originally written on spec for Wyrd Science magazine.

The header is a mashup of images by giannsartori and Kelly. Both are open license.

Related posts

Callers, Multilogue, and the GM as Ant Queen

More musings on communication and structure in TTRPGs

Table Talk

TTRPGs as communication & communication in TTRPGs

Revaluating RPGs, Abridged

A summary & discussion of my paper about RPGs and art

3 thoughts on “Reminiscences of the Future, Part 2: A Theory of Gaming”