If you’re a tabletop gamer, you’ve probably spent at least a few minutes of your life trying to explain roleplaying games to the uninitiated. Maybe you were trying to entice a friend to join a session. Maybe you were just trying to explain the genre to an unwitting bystander.

Whatever the case, you may have talked about playing characters akin to acting or improv. You may have mentioned randomization tools such as dice, likening it to a game of craps. You may have compared running a game to writing a story or making a short film.

These are all useful analogies and enlightening in their own capacities. But on their own, none capture the whole nature of roleplaying games, and taken together, they can seem like a bricolage of disparate media instead of a unified, satisfying explanation.

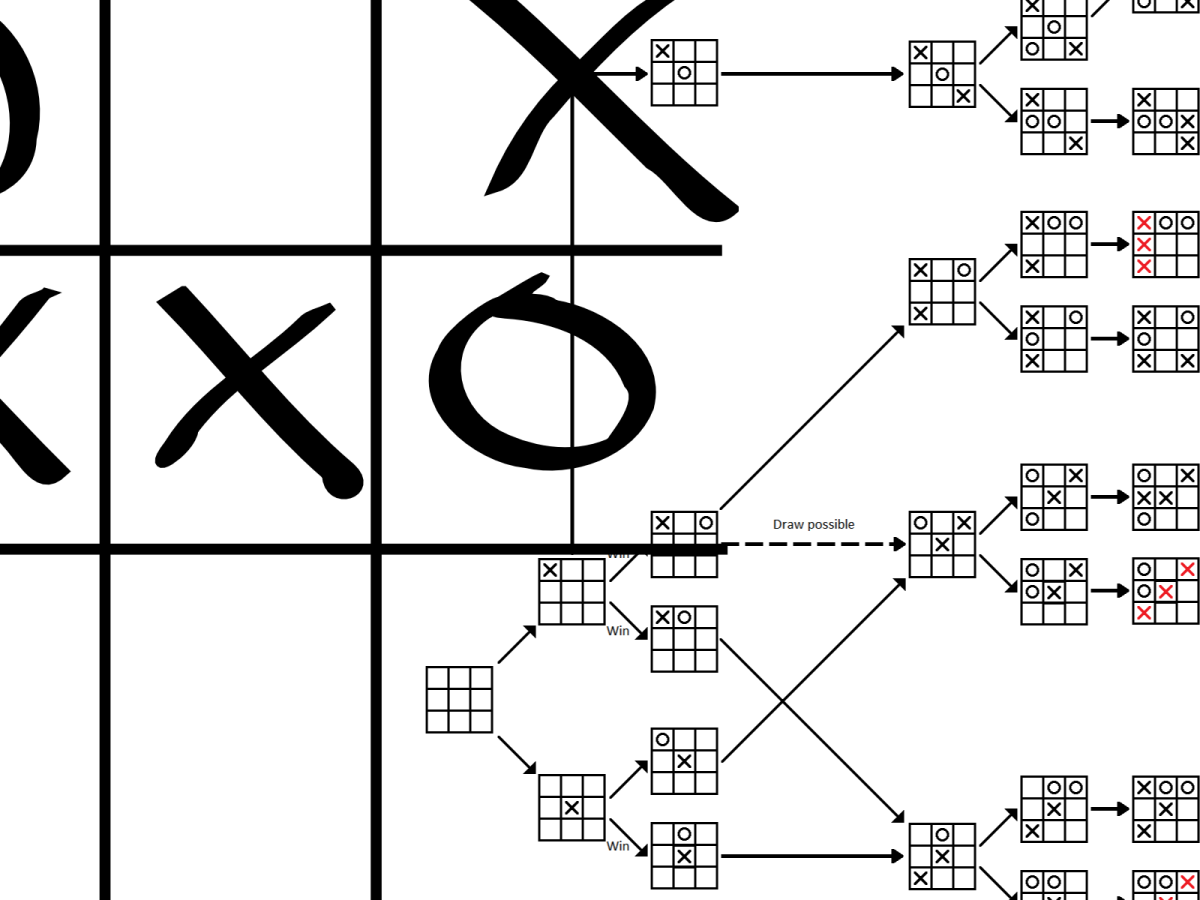

The challenge isn’t limited to explaining RPGs to outsiders. It’s just as tricky to look in the mirror and try to clearly define what designers and their games are doing. The difficulty is attested by the huge body of literature, both academic and popular, attempting to clearly define RPGs and what sets them apart from other types of games. (You can read some of that literature, and get links to more, in my RPG theory reading list.) Despite much discussion, the fact remains: various types of RPGs possess variegated features that make the genre a tricky beast to pin down.

But most gamers agree that they can point to an RPG when they see one. So instead of trying to engineer an explanation for non-gamers, why not instead answer that thorny question “What is an RPG?” with an example?

Epidiah Ravachol—living up to his reputation as a “creator of unconventionally sized & shaped role playing games”—takes exactly this approach in his appropriately titled What Is a Roleplaying Game? The size is one single page, and the shape is a didactic game designed to demonstrate what RPGs are, how they are played, and what happens to them afterward. Instead of an explanation, it instructs the experience and empowers the curious to learn firsthand.

The document is less a set of rules than a procedural instruction manual. The first four points involve setting the stage, and the second four are guidelines for playing out each scene. By no means does the game offer up any kind of comprehensive technical definition, but it fulfills its mission more effectively than any long-winded essay could ever aspire to.

But that’s not going to stop me from writing about it.

A Roleplaying Game Is …

“It is a game you play with friends in a social setting.”

Straight away, the game establishes itself as a social activity. It also implicitly gives you a “what you need to play” list: some friends and comfy seats.

“It’s a chance to be someone you’re not.”

Now that you know what you need to play, you find out what you’ll be playing. The game’s concept is simple: a group of astronauts rob a bank right before launching into space. Most of us are neither astronauts nor bank robbers, and as far as I know, no one else in history has ever been both. So the game certainly delivers on the promise of being someone you’re not.

Someone may ask: Why are astronauts robbing a bank? Where are they going to spend that money—SpaceMall? Irrelevant questions, all. Roleplaying games, like all games, are windows into worlds that operate according to their own logic, and the fun of RPGs comes from inhabiting those worlds for a little while.

“It’s a celebration of sticky situations.”

Conflict. Risk. Reward. These are the engine of every game (and every story), and WIaRPG? emphasizes active engagement by dropping the players in mid-action. It does so with a very simple set of prompts: who’s there, what’s happening, and what’s already gone wrong.

“It’s collaborative daydreaming.”

With a tense, exciting situation established, the game gets granular. One astrorobber becomes the focus, and the others take on the roles of the other astrorobbers and supporting cast—essentially sharing the work of a GM and letting the in-focus player concentrate on their own character.

“It’s exercise for your personal sense of drama.”

Here the game introduces a formal means of resolving conflict. The first step is simply recognizing when a player narrates something difficult or risky. A story or a game without adversity quickly becomes boring. When it pops up in play, it’s an opportunity to build tension and make the game more interesting for all involved.

“It’s a way to trick ourselves into creating interesting things.”

After one player does something hard or potentially harmful and a second player calls them on it, a third player steps in to arbitrate the consequences and collateral damage (again distributing traditional GM duties amongst the group). And if the proposed action is both hard and harmful, tragedy strikes, the scene ends, and a new character comes into focus. The cycle repeats until the plot reaches a logical conclusion, giving plenty of motivation for players to watchdog whoever’s in the spotlight and maneuver themselves back toward center stage.

“It’s something you’ve been doing all along.”

If you’ve gotten this far, then congratulations! You now have firsthand experience with RPGs, and you have a better idea of what they’re all about. And now that you get it, you can keep going—by continuing to do the things you’re already doing.

Postgame

WIaRPG? is a brief, nontechnical, fairly informal, and easily navigable document that facilitates an experience with the same qualities. It provides easy access to RPGs, and does so beyond just playing them.

On the game’s landing page, Ravachol takes his instruction to the next level by explaining how to steal his work and get away with it. He describes the Creative Commons license the game is published under, how it grants the right to adapt and redistribute the game, what constitutes a non-superficial alteration that entitles a person to credit themselves (rather than the original creator) as author, and how it can be republished for profit.

This is a lesson in rights and publishing, sure—but it’s also one more lesson about RPGs. Ravachol teaches his players how to take what they like from a game they like and get away clean.

Just like an astrorobber making off with a load of cash.

WIaRPG? is about that particular conceit, but it’s ultimately (and covertly) also about the nature of adaptation, game design, and RPGs as a fluid, mutable, participatory cultural form. It’s about how designers and players—separately and simultaneously—tweak them and hack them and reskin them, keeping the things we like and rewriting the rest. And then we send them back out into the world to be played by others.

All images and quotations were created by Epidiah Ravachol and are used here under CC BY-NC. You can download them along with the rest of What Is a Roleplaying Game? for free at Dig a Thousand Holes.

Liber Ludorum is entirely reader-funded. Please consider lending your support.

Related posts

Analyses of the Unreal

A curated reading list of TTRPG theory for designers, players, and thinkers

Roleplayer’s Dilemma

Making tough choices in RPG theory and game theory

Recent posts

Breakout Con ’24: a retrospective

Impressions of Canada’s largest tabletop gaming convention

Tabula Rasa: a (p)review

An exclusive first look at the groundbreaking rules-minimalist, experience-maximalist TTRPG

Games & Systems

The tradeoff between flexibility and direction, and the pitfalls of thinking about both